The Dive bezel: Its history and its use

by Jason Heaton

Sitting on the gunwale in a pitching sea, 80 feet above the reef, a diver wriggles into his tacky rubber suit and heavy fins. After spitting in his oval mask, he awkwardly shoulders a cylinder of compressed air, cinches his belt of lead weight and puffs in his twin-hose regulator. On one wrist, a compass and depth gauge; on the other, a dive watch, its luminous dial soaking up the tropical sun’s rays. He glances over his shoulder one last time, then reaches down to spin the rotating bezel on his watch, aligning its zero marker with the minute hand, then presses his mask to his face and rolls back into the Caribbean. This is scuba diving, circa 1957.

The rotating bezel is the hallmark feature of the dive watch, recognizable from a distance and so elemental that it seems like it has always existed, evolved like the perfect dorsal fin of a pelagic predator. But in fact, this simple component first made its appearance on underwater watches in the early 1950s out of necessity, at the behest of those early scuba divers who needed a way to track their bottom time. Since then, the dive bezel has changed, been improved, taken on myriad forms and now, ironically, is scarcely used for the purpose for which it was devised. But even though digital dive computers have largely supplanted analog watches on wrists of divers, the dive watch and its signature feature remain as popular as ever, more as a symbol of adventure and rugged functionality.

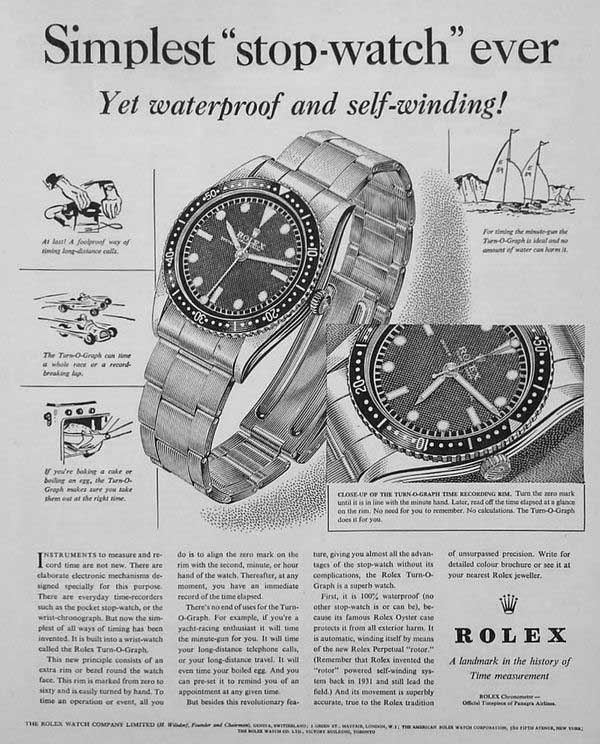

There were diving watches and rotating bezels well before the 1950s. Rolex put a large rotating bezel on its ultra-rare Zero-graph in the 1930s and it was during that decade that Officine Panerai was selling sturdy underwater watches to the Italian Navy for its combat divers. But the first truly purpose-built diving watches to feature rotating bezels debuted in 1953, when Blancpain, Rolex and Zodiac all introduced watches that would become the archetypes for all the diving timepieces to follow. So why did the rotating bezel become de rigueur for diving watches, a feature that even made its way into ISO 6425, the international standard that governs what can be considered a dive watch? To understand that, perhaps it’s best to step back and look at how and why these timing bezels are used in the first place.

The Rolex Zerographe ref. 3346 was the first recorded wristwatch with a rotating bezel (circa 1930s) (Image: phillips.com)

A Rolex ad for the Turn-O-Graph, their first production dive watch with a rotating bezel (circa 1950s) (Image: phillips.com)

Jason Heaton diving in the Florida Keys with the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms Tribute to Aqua Lung (Photography: Gishani Ratnayake) (Image: revolutionwatch.com)

“Bottom time,” or the time spent underwater, is critical for a diver to track. This is because there is a maximum number of minutes a diver can remain at each depth before a buildup of compressed nitrogen in his body tissues exceeds safe limits. If this happens, he cannot ascend directly to the surface without pausing partway up to decompress, or “off-gas,” the nitrogen. Hence, a diver must pay attention to the “no-decompression limit” for each depth. A common mnemonic is the “120 Rule” which states that 120 minus the maximum depth (in feet) will equal the number of minutes that can be spent there. So on an 80-foot dive, the no-decompression limit is 40 minutes, as read off of his watch’s bezel.

Of course, should a diver exceed the no-deco limits, he must pay an underwater penalty of sorts and remain at different depths for several minutes on his way to the surface (and hope he has enough air in his tank) to decompress. These intervals also need to be tracked by the watch and the bezel is once again called into action for these shorter time frames. For this purpose, it is the hashed minutes demarcated on most bezels’ first 15 or 20 minutes that become useful.

Blancpain was the first company to make its timing bezel unidirectional, only ratcheting counter-clockwise. A unidirectional bezel is useful since, should it get bumped during the rough and tumble of diving, it will only subtract time from a diver’s bottom time and not put him in danger of overstaying his no-deco limit. Until Blancpain’s patent ran out on this feature, other brands had to make do with bezels that spun both ways. Today, unidirectional bezels are virtually universal.

In 2017, dive watch bezels may not be used much for timing dives or tracking no-decompression limits. But they can still be useful to a diver, such as in navigation, when timing a swim distance is crucial, or for tracking the time between dives (the “surface interval”). And of course, should a battery-powered dive computer fail, on the wrist of a diver who remembers his “120 Rule” a traditional dive watch can still save the day. But beyond these uses, the dive watch is the calling card of the diver, a symbol of this community of adventurous people who still explore the world underwater. And the feature that makes a watch a dive watch is, of course, the rotating bezel.

Original: https://revolutionwatch.com/dive-bezel-history-use/